Ancient Egyptians may have tried to treat cancer with surgery more than 4,000 years ago, a study has revealed.

The findings were published in May in the journal Frontiers in Medicine and add to a growing body of work seeking to expand our understanding of how one of the world’s most important civilizations tried to tackle diseases, especially one as deadly as cancer.

Why is this discovery significant?

Researchers have long known that medicine in ancient Egypt was more advanced than in many other ancient civilisations. Some of the earliest references to physicians date back to that period with procedures like bone setting and dental fillings common practice.

The extent to which its doctors may have attempted to examine and treat malignant brain tumors was unknown to experts until recently.

Researchers examining historical skulls claim to have discovered tangible proof of invasive brain tumor surgery, demonstrating that doctors were attempting to expand their knowledge of the illness known as cancer. The finding might possibly represent the earliest instance of the disease’s surgical treatment in ancient Egypt.

As a palaeopathologist studying ancient diseases at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, lead author Edgard Camaros told Al Jazeera, “Our research observes, by looking directly into human bones with cancerous lesions, that they performed an oncological surgery.” “We’re not sure if this was a possible surgical intervention, a medical exploratory autopsy, but unquestionably an oncological procedure to gain a deeper understanding of what is now known as cancer.

Researchers Albert Isidro of the University Hospital Sagrat Cor in Spain and Tatiana Tondini of the University of Tubingen in Germany co-authored the study with Camaros.

How did scientists discover evidence of ancient surgery?

Two skulls, each thousands of years old, provided the evidence that both general healing treatments for head injuries and more specific cancer surgeries were undertaken in ancient Egypt.

Both were originally discovered in Egypt in the mid-1800s and are now part of the University of Cambridge’s Duckworth Laboratory skull collection in the United Kingdom, having been taken there by archaeologists for research.

New evidence that surgeries had been carried out became visible in October 2022 by using advanced technologies such as microscopic analysis and computed tomography (CT) imagery, which is usually used in medical treatment to create detailed internal images of the body.

One skull, number 236, is thought to date from 2687 BC to 2345 BC and belonged to a guy who was between 30 and 35 years old. Its scarred surface showed roughly thirty lesser lesions scattered across it, as well as one major lesion thought to be from a malignant tumor. Around the lesions, researchers discovered cut marks that may have been created with a sharp metal object.

According to a statement from Tondini, “We wanted to learn about the role of cancer in the past, how prevalent this disease was in antiquity, and how ancient societies interacted with this pathology.” “We were astounded by what we saw when we first looked at the cut marks under the microscope.”

The precise purpose of the incisions are not clear, and it is not known if the subject was dead or alive at the time. If the cuts were made posthumously, Camaros explained, then it could point to the fact that the physicians were conducting experiments or performing an autopsy.

If the patient was alive at the time, then the cutters were more likely trying to treat him. Without the patient’s medical history though, there is no way to be sure.

The second skull, labelled 270 and dating from 664 BC to 343 BC, is believed to be from a woman who was older than 50. It, too, has lesions believed to be from cancerous tumours although there are no signs of attempts to treat or observe it.

However, skull 270 has healed fractures from what was likely severe trauma from a weapon and continued to live long after those fractures were sustained. The fact that the individual survived could point to some form of successful medical treatment although it is unclear what that might be.

What else is known about cancer in ancient Egypt?

Ancient Egyptians believed diseases were a punishment from the gods, but they were nonetheless adept at medical care, using fresh meat, honey, lint and a host of herbs to treat wounds, for example. There were enough physicians in ancient Egypt that most were able to focus on one disease specialty, it is believed.

Ancient texts have already demonstrated that cancer was probably not one of the ailments they understood well enough to cure, however this does not mean the illness did not exist at the time. Due to the scarcity of cancer cases in fossil records, there was once a widespread idea that pollution and dietary or lifestyle changes in the modern world were the primary causes of the disease, which is currently the second largest cause of death worldwide.

However, the researchers added that this most recent result, together with others in recent memory, has made it clear that cancer was likely more widespread in the past than previously thought.

According to Camaros, “cancer is not a modern disease, although age and lifestyle are important factors that increase its incidence.” As old as time itself, cancer is connected to multicellullar life, and as a result, cancerous disorders have plagued humans from the outset. It is crucial to consider the possibility that cancer was far more common than previously believed.

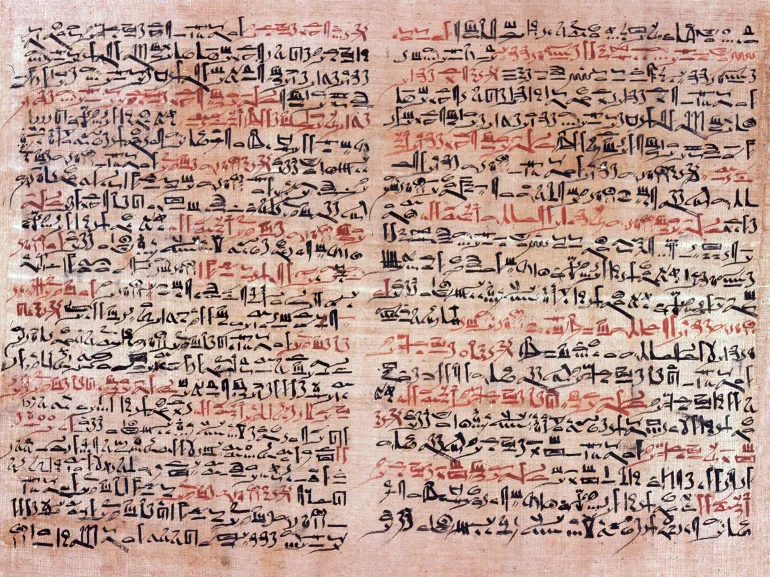

In fact, early observed cases of cancer are believed to have been documented in an ancient Egyptian medical text now known as the Edwin Smith Papyrus. The 3,600-year-old document did not use the term “cancer” but there is little doubt among scientists that the “untreatable grave disease” it refers to is the same one scientists are still trying to understand and cure today.

Still, we know ancient Egyptians could diagnose cancer. They did this by looking at or feeling swellings and classifying them according to their characteristics – breast tumours with pus or tumours exhibiting redness, for example. Tumours were also classified by their feel, such as “hot” or “cold” tumours, historians said.

Ancient Egyptian physicians also pursued treatment, if not cures, for the disease, using cauterisation – burning off undesirable tumours – and bandaging them with therapeutic herbs for relief, according to the Edwin Smith Papyrus.

[…] Did ancient Egyptians use surgery to treat brain cancer? […]